Cavete: discusses and links to material some people may find disturbingWhen I was in my mid-teens I developed acne. Never having been one to do things by halves, mine was in the form of angry boils flowering luxuriantly over my fizzog. I didn't have much of a problem with it, and didn't get more hassle than one might have expected in a working-class Glaswegian housing estate.

Then I went to university in Italy, and the head of my college decided he

did have a problem with my acne, and at his insistence I set out on courses of antibiotics and various other pills and potions - one of which, as I remember, turned my first wee of the morning bright red, which was quite a thing if you weren't prepared for it.

During my first year at uni I fell into a deep depression, and I wonder if the head's effective declaration that my appearance was undesirable contributed to the mix of being away from home from the first time and studying like I'd never done before. But the past can be a dangerous place to form assumptions about, so who knows?

I found myself thinking about this period of my life for the first time in a while after an advert directed me to BBC Radio 1's listen-again feature, where

Aled Jones from the Chris Moyles show (me neither) had hosted a "surgery" about body-image, when a young man called in to speak about his desperation that nothing his doctor gave him was touching his acne. I felt for him.

An American psychotherapist called Aaron Haydn Jones explained the process of filtering, whereby we might ignore 100 positive comments and dwell on one negative one. I can't argue with that - Richard Carpenter attributed one journalist's comments about his sister's weight in the early 1970s to her tortured death in 1983.

The show, however, wasn't exclusively about anorexia and bulimia as such but about unhappinesses with one's body (which might admittedly feed the pathogenesis of one of these terrible illnesses). I started to wonder about the direction of the show when one chap rang in to complain about the shape of one of his eyebrows, but then a young woman said that she'd had problems with her mum after she (

filia) had a breast reduction: Aaron was running with the ball immediately, and wondered if the girl had had cosmetic surgery for what was a relational problem, and spoke of feelings of jealousy - or at least displacement - that can sometimes occur between mother and daughter, father and son. Then, of course, another young woman rang in to complain that her breasts were too small.

Something that's been in the news recently is airbrushing - a case in point being a photo of model Phillipa Hamilton where her waist appears smaller than her head, an image that made fashion house advertisers Ralph Lauren regret their use of Photoshop and ultimately issue a reluctant apology. To indicate the power of the program, some Radio 1 figures allowed their

images to be retouched and posted on the website.

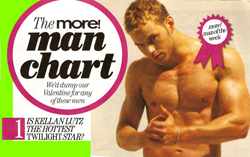

Where things started to get interesting was when Emma Ledger, deputy editor of

More clebrity magazine, came on the show briefly to say that the publication had no policy as to the sizes of models whose photos it published, and that it only airbrushed to get rid of zits or tidy up hair. "Who wants to see a zit on the cover of a magazine?" she moaned, and suddenly I realised that perhaps punk had a point after all.

The first thing I did was to reflect that if a mag is publishing pics of clothes that are supplied to it, its in-house policies on model sizes are meaningless if the sample garments supplied to

it only fit "size-zero" models; something which caused (British)

Vogue editor Alexandra Schulman to

fire off an angry letter to designers.

The second thing I did was to buy a copy of

More, and try not to look too embarrassed as I payed for it. This is something I did when suspicious about

Now editor Abigail Blackburn's protestations of innocence to Louise Redknapp, who had accused her magazine of triggering "

pregorexia; the issue of

Now

brought out to coincide with Redknapp's crusading documentary was a celebrity pregnancy special, but the devil was in the detail, and the detail turned out to be in the back issues.

I have no back issues of

More, but on flicking through the magazine did find an advert for Tesco Clothing Online featuring a photo of a woman who looked as though she had other priorities than eating. Had the magazine been supplied with the pic, or with clothes that would only fit somebody of her dimensions?

What caught Maxima's eyes made a bee in her bonnet buzz furoiusly: she pointed to a photo of Sarah Harding of Girls Aloud with (I think) Tom Crane, and, pointing to Crane's form (which compared to mine looks skeletal), demanded to know why men could look any way they wanted while women had to look like Barbie. At least she let up quite soon - one Hogmanay she went on and on about male performers looking like they'd been dragged through a hedge while female ones were expected to exude glamour. At least s

he had a point. But I hope the bloke who phoned in to complain about his eyebrow never had a look at the "

More man of the week" (Kellan Lutz from vampire flick

Twilight); no wonder illicit steroid sales are booming, as vulnerable young men think they have to "get ripped". It's not for me to contradict Emma Ledger and say that the photo was digitally manipulated, but Radio 1 DJ Vis showed that it could be done (see pic below).

Ledger did stress that her magazine was for 18-26-year-olds ("of all shapes and sizes"), but the feature that gave me most cause for concern was nothing to do with body-image, rather "position of the week", demonstrated with Barbie and Ken dolls. I thought of the poor girl who texted Jones' show to say that she only felt good about herself if a boy told her she was pretty, and felt furthermore that the only way to bring this about was to sleep with said boy. I remembered sadly the travellers' tales of former colleagues in drugs work, who had given talks to schoolchildren and reported back that girls said that some boys threatened to spread the word that they were "frigid" if they refused to have sex. Sometimes we fellows are unconscionably nasty people, and moreover, while

More is by no means the worst offender, I'm also not sure what Ms Ledger thinks happens to somebody on their 18th birthday to make them less vulnerable to masculine con-tricks than they were at 17 years and 364 days old.

Now I only look in the mirror on those occasions when I have no choice but to shave and comb my hair; but I remember a strange young man who would examine his image, although I'm no longer sure what he was looking for or even at. Young people today are not the means to enrichment of the staff of celebrity magazines and/or the shareholders of companies that own them. It's no cliché that children are the future: young people will father and bear our grandchildren, will work in supermarkets and universities and, among a milion other things, will hopefully enjoy life enough to convince the grumpier among us that there's a point to it all.

And, on a personal note, I'd like to send a message to the young man with acne. Nothing worked for me either - but it faded in every way as I got older.

Related posts:

Abigail Blackburn and the truth about pregorexia

Claire Sweeney's big fat...

Last Friday John Smeaton, director of SPUC (the Society for the Protection of Unborn Children) drews a line in the sand in response to the Government's abusive proposals for sex education in schools, which bode ill for the Christian, Jewish, Hindu and Muslim voluntary grant-aided

Last Friday John Smeaton, director of SPUC (the Society for the Protection of Unborn Children) drews a line in the sand in response to the Government's abusive proposals for sex education in schools, which bode ill for the Christian, Jewish, Hindu and Muslim voluntary grant-aidedme in conjunction with the RE syllabus...the school explicitly recognises the reality that some young people may choose to be sexually active and, if that is the case, they need the knowledge and confidence to make an informed choice to protect themselves from pregnancy and STIs. The school nurse provides students with clear accurate information about the full range of contraception and STIs and details of local services...Pregnancy options, including abortion, are also discussed in a non-judgemental way with the RE syllabus requiring students to understand the spectrum of pro- and anti-choice views on abortion.

Later that day, the Telegraph's Blogs Editor, Damian Thomson forecast Bad Things for Oona Stannard, chief executive of the Catholic Education Service, which, as Smeaton identified, had helped the Government draw up its guidelines. Fr Tim Finnegan, a frequent flier on this feature, refers to both posts as he runs with the theme on his blog The Hermeneutic of Continuity. He asks how far the moral relativism will be taken:

Later that day, the Telegraph's Blogs Editor, Damian Thomson forecast Bad Things for Oona Stannard, chief executive of the Catholic Education Service, which, as Smeaton identified, had helped the Government draw up its guidelines. Fr Tim Finnegan, a frequent flier on this feature, refers to both posts as he runs with the theme on his blog The Hermeneutic of Continuity. He asks how far the moral relativism will be taken:  es, today - Tuesday 23 - is the day when Parliament is due to vote on what is effectively the nationalisation of the bodies, minds and spirits of our children.

es, today - Tuesday 23 - is the day when Parliament is due to vote on what is effectively the nationalisation of the bodies, minds and spirits of our children. to Africa.

to Africa.

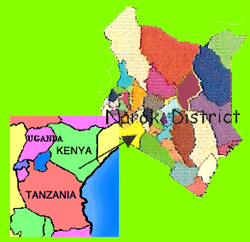

The Maasi is a true pastoralist. Farming is anathema to them. They are hospitable, generous and affectionate, love their children, unbelievably domestic and gentle, and religious. They are firm believers in the one God - Engai, but are plagued by a fear of evil spirits. Bravest of the brave, a warrior tribe living the life they have lived over hundreds of years.

The Maasi is a true pastoralist. Farming is anathema to them. They are hospitable, generous and affectionate, love their children, unbelievably domestic and gentle, and religious. They are firm believers in the one God - Engai, but are plagued by a fear of evil spirits. Bravest of the brave, a warrior tribe living the life they have lived over hundreds of years.  ng - and more. Maasai Medical Mission aims to play a part in bringing God's love and care to some of the poorest people in the world.

ng - and more. Maasai Medical Mission aims to play a part in bringing God's love and care to some of the poorest people in the world.

hree hymns from the top ten wedding hymns during the service - Amazing Grace, Make me a Channel of your Peace and Praise my Soul the King of Heaven. Between the second and third the married couples faced each other and renewed our wedding vows, saying "I took you..." and "with this ring I wed you...", etc. With a peal of bells beforehand and a slice of cake and glass of champagne or orange juice afterwards, it was good to touch home with where we'd started out all those years ago - scrape off the barnacles, as it were.

hree hymns from the top ten wedding hymns during the service - Amazing Grace, Make me a Channel of your Peace and Praise my Soul the King of Heaven. Between the second and third the married couples faced each other and renewed our wedding vows, saying "I took you..." and "with this ring I wed you...", etc. With a peal of bells beforehand and a slice of cake and glass of champagne or orange juice afterwards, it was good to touch home with where we'd started out all those years ago - scrape off the barnacles, as it were.

brought out to coincide with Redknapp's crusading documentary was a celebrity pregnancy special, but the devil was in the detail, and the detail turned out to be in the back issues.

brought out to coincide with Redknapp's crusading documentary was a celebrity pregnancy special, but the devil was in the detail, and the detail turned out to be in the back issues. he had a point. But I hope the bloke who phoned in to complain about his eyebrow never had a look at the "More man of the week" (Kellan Lutz from vampire flick Twilight); no wonder illicit steroid sales are booming, as vulnerable young men think they have to "get ripped". It's not for me to contradict Emma Ledger and say that the photo was digitally manipulated, but Radio 1 DJ Vis showed that it could be done (see pic below).

he had a point. But I hope the bloke who phoned in to complain about his eyebrow never had a look at the "More man of the week" (Kellan Lutz from vampire flick Twilight); no wonder illicit steroid sales are booming, as vulnerable young men think they have to "get ripped". It's not for me to contradict Emma Ledger and say that the photo was digitally manipulated, but Radio 1 DJ Vis showed that it could be done (see pic below).

I was never a sports fan; but it's so pervasive that, even being averse to it if not phobic, I was caught up by the cloud of depression caused by Kenny Dalglish's departure to Liverpool from Celtic that hung over our school for a day. I think I went home and gazed at his picture on one of the football cards you got with bubble-gum bro

I was never a sports fan; but it's so pervasive that, even being averse to it if not phobic, I was caught up by the cloud of depression caused by Kenny Dalglish's departure to Liverpool from Celtic that hung over our school for a day. I think I went home and gazed at his picture on one of the football cards you got with bubble-gum bro

For example, we had the infamous

For example, we had the infamous  Robinson, MP in the devolved Stormont Assembly in Northern Ireland, who had a fling with one man who fleeced her for £50,000, told all in a BBC documentary and is now a

Robinson, MP in the devolved Stormont Assembly in Northern Ireland, who had a fling with one man who fleeced her for £50,000, told all in a BBC documentary and is now a