The latter contained a poem called Jabberwocky, concerning the hunt for and killing of the Jabberwock by an unnamed protagonist who is addressed by the poem's narrator as "my son". I was introduced to this poem in school and still remember the rather scary "snicker-snack" of the vorpal blade. I had actually met the titular creature before in a children's book called The Jabberwock in which it was presented as an altogether more friendly creature, although I've never been able to find it since. I must say, though, I do like the toves - creatures who are part badger, lizard and corkscrew, who live under sundials and eat cheese. That's my kind of wildlife.

The poor Jabberwock has since largely fallen out of the public consciousness, even though the first verse of the poem which gave him life appeared in a short story called "Mimsy were the Borogoves by husband-and-wife team Henry Cuttner and C.L. Moore under their pseudonym Lewis Padgett, in the classic American magazine whose time-worn issues I used to hunt in fairs in Glasgow, Astounding Science Fiction Magazine (later known as Analog):

'Twas brillig, and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe;

All mimsy were the borogoves,

And the mome raths outgrabe.

It turns out that the first verse, taught to Alice Liddell by her "magic toys", is a set of instructions in how to connect flotsam so that it will conduct the Paradine children to Unthahorsten's dimension "in fragments, like thick smoke in a wind...in a direction Paradine [pater] could not understand". Paradine and his wife, as has been explained by child psychologist Holloway, have been "conditioned" to think in Euclidean geometry, while children's minds are so unconditioned as to be alien territory to adults.

I loved the story. My favourite period for American sci-fi is from the mid-fifties to the mid-seventies, but there were publications like Astounding Science Fiction who had been releasing intelligent output by writers conversant with science for more than a decade beforehand. What really impressed me about Mimsy were the Borogoves was that the authors drew upon Carroll's 1879 work Euclid and his Modern Rivals, written to defend Euclid against emerging theories of non-Euclidean geometry, and placed it in the context of the counterintuitive theories offered by 1940's quantum physics (whose seductive appeal remains to be consummated). The story's "crazy angles" certainly feel more comfortable than the "obscene angles" put to work upon the doubtful agendas of HP Lovecraft's corpus.

Where all this is leading is that today I watched The Last Mimzy with Minima. It was, supposedly, based on Mimsy were the Borogoves and so could be said to be related to the poor forgotten Jabberwock. In this version, however, the childish mutidimensional being is replaced by a desperate scientist from a future time when humanity's genes have become so poisoned that life in the open air is unimaginable without toxin-filtering exoskeletons.

The box sent back through time is spotted by five-year old Emma Wilder and recovered by her brother Noah, who is taught by a piece of perspex to speak in such a way as to make spiders alter the way in which they spin webs. His sister adopts the teddy-bear Mimzy (sic), but she is introduced to Jabberwocky by her babysitter, who flees when Emma makes some stones spin in mid-air then atomises her arm inside the circle formed inside them. If you're lost, then you're on the right track.

In the film, Holloway is replaced by Larry White, (eleven-year-old) Noah's science teacher, representing a dumbing down in every way. He is passionate about the abuses wrought upon nature by poisons created by humankind, which he summarises by displaying a two-headed snake preserved in formaldehyde. Call me reactionary, but I would have shown the kids the effects upon humans of, say, the Bhopal disaster, which would have given them much-needed nightmares while removing the risk of them being near formaldehyde.

A unique element in The Last Mimzy is the Mandala, which is a series of ornate patterns contained within a circle pioneered by Buddhists, but also used by Hindus. White's partner is seen chanting in a Buddhist fashion in front of Hindu icons, so presumably we are meant to assume that "it's all the same thing". As in Mimsy were the Borogoves, the toys instruct the children, but there's no knife-edged disappearance. It's all rounded corners and warm fuzzy assurances that everything will be okay. Okay, that is, as long as we stay away from major centres of population like Seattle and the big bad enforcer of the Patriot Act (the only major black character in the film).

In the film, Mimzy is not an anatomy-doll but is found to be an impossibly sophisticated artificial life-form with the legend Intel inscribed at a level only an electron microscope can detect. Having escaped from a high-security US installation, Emma's tear lands on Mimzy. Noah, who Emma describes as "my engineer", enables the toy to be returned to the future, and suddenly an industrial dystopia becomes the garden of eden redux, which allows a boy and girl to shed their exoskeletons and head outside, the light obliterating their near sides so that they look like two halves of the same person.

I was left feeling empty and unsatisfied by the film for the same reasons that I am left feeling insulted and patronised by much of what passes for modern science. I realise it might be mischevous of me to suggest that scientists started to sound like theologians some decades ago because they were merely occupying ground vacated by some theologians; but it seems strange to me that on the subject of whether climate change is predominantly due to the activities of humankind, for example, so-called scientists waste public money labelling freer thinkers than themselves as equivalent to holocaust deniers, people who deny the link between HIV and AIDS and irresponsible drivers.

If establishment scientists spent time doing science, they might have discovered that the oceans are rising faster than computer models before the free thinkers, because the latter spend at least as much time in the real world as sitting in front of computer models.

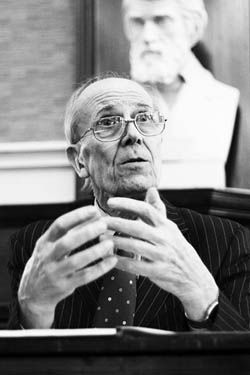

And if idealogues like Richard Dawkins, whose declamations upon religion from a strange dissociated place that makes ivory towers look pedestrian, would stop inficting their histrionic agendas upon the media, we'd be spared from having to examine our children's videos for ideas like that, expressed at the end of The Last Mimzy, that the genotype determines the soul. Get real, guys.

And let's have a cheer for the Jabberwock.

y at Orth-Donau, Austria got conspiracy theorists so excited they practically went into orbit when it sent

y at Orth-Donau, Austria got conspiracy theorists so excited they practically went into orbit when it sent  vaccines at a time when responsible scientists desire to use cell-lines from other sources than human beings who have not been in a position to consent or otherwise to their use. Whether you want to look at it from the point of view of the Catechism of the Catholic Church's statement that "

vaccines at a time when responsible scientists desire to use cell-lines from other sources than human beings who have not been in a position to consent or otherwise to their use. Whether you want to look at it from the point of view of the Catechism of the Catholic Church's statement that "

England can't claim such a high-profile patron saint as, say, the US, which is represented by the Immaculate Conception. (The

England can't claim such a high-profile patron saint as, say, the US, which is represented by the Immaculate Conception. (The

enophobia. But the aspect of multiculturalism that warms my heart most is that represented by Sri Lankan-born postmaster Deva Kumarasiri who,

enophobia. But the aspect of multiculturalism that warms my heart most is that represented by Sri Lankan-born postmaster Deva Kumarasiri who,

ing unwilling to turn down applications for a loudspeaker-system in a Mosque, that Muslims be invited to turn their minds to Allah

ing unwilling to turn down applications for a loudspeaker-system in a Mosque, that Muslims be invited to turn their minds to Allah

I'm sitting here listening to a BBC Radio 2 programme commemorating the 250th anniversary of Messiah coposer George Frederick Handel, which concentrates on that most famous of his oratorios; we're waiting for At the Foot of the Cross presented as a meditation "of words and music" on Good Friday by Ken Bruce, featuring excerpts from Messiah.

I'm sitting here listening to a BBC Radio 2 programme commemorating the 250th anniversary of Messiah coposer George Frederick Handel, which concentrates on that most famous of his oratorios; we're waiting for At the Foot of the Cross presented as a meditation "of words and music" on Good Friday by Ken Bruce, featuring excerpts from Messiah.

I'm trying to get over a period of not having gone to church. I'm it sure how it happened, but I realised recently that suddenly not going to church had become as normal to me as going had quite recently been.

I'm trying to get over a period of not having gone to church. I'm it sure how it happened, but I realised recently that suddenly not going to church had become as normal to me as going had quite recently been.

It's a story I came to through

It's a story I came to through

Here we go again.

Here we go again. mear its own constituency of licence-fee payers for not being quick off the mark about complaining, which probably reflected Brand's miniscule audience more than anything else; but when journalists, notably the Mail's

mear its own constituency of licence-fee payers for not being quick off the mark about complaining, which probably reflected Brand's miniscule audience more than anything else; but when journalists, notably the Mail's