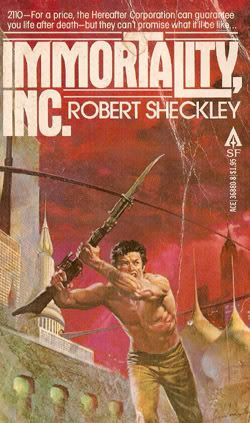

Immortality, Inc.

Robert Sheckley

ACE 1959

pp 279

(Also published in 1958 as Immortality, Delivered)

I love sci-fi novels from the mid-50s to the mid-70s, where through looking at the author's vision of the future one sees a view of where the future might be going. Towards the end of the '70s the sci-fi market started to be saturated with various Star Wars and Star Trek novelisations and spin offs which, while being fair reads individually, became cumulatively rather too much of a good thing.

Robert Sheckley's novel of temporal bodysnatching is filled with the sort of humour acting as a trojan horse for piquant social comment that earned him the accolade of "Voltaire and Soda" from fellow sci-fi writer Brian Aldiss.

Thomas Blaine dies in a collision with another car, having driven his rather aggressively. He awakes in a clinic, rather disorientated - understandably - and finds recording technicians commenting positively on the quality of his anguish which they have been saving on a disc that will go on general release, so others can vicariously experience his trauma from inside his head then return to the safety of his living-room.

It turns out that the Hereafter Corporation has been experimenting with grabbing people from the past to solve the problem of "zombies". These result when the mind of a paying customer cannot bond properly with the body of somebody who has been given Hereafter Insurance as the price for selling his body for the customer's continued corporeal existence.

The premise of the book is that a way has been discovered of detecting the mind after death, the backstory that following this revelation, people started to sate their appetites for all sort of risky activities in the belief that death is not the end - deceived by false hope: it is not guaranteed that everybody's mind will cross over.

Which is where the Hereafter Corporation steps in, having found scientific methods to virtually guarantee not only the survival of the mind in the, well, hereafter, but also the transfer of a mind from a body that is in some way unsatisfactory to another model. Poorer individuals sell their bodies for money that will pay their families' bills and the aforesaid insurance. For especially lucrative customers the transfer is done in a clinic, otherwise...Sheckley describes a queue of sad individuals waiting to do their deal in a "suicide booth".

Blaine finds himself in the body of the proto-Chippendale we see on the book's cover and, when he is unable to reprise his career as a junior yaught designer, becomes a hunter, being paid to provide a showstopping finale for those who have been there, done that, and, having paid up their policies, are tired of a priveleged life. Free to do this because Hereafter have decided that it would be too controversial to use Blaine as marketing material, he finds that he is now hunted. With a love story and the de rigeur slipping of a mickey in a bar, it's a thoroughly entertaining and challenging novel, no less so than at the ending.

It seems to me, though, that our materialistic culture hasn't diverged much from the path Sheckley foresaw in novelised form. We can't yet see the world from inside other people's heads, but TV schedules are creaking with reality shows filmed 24/7 from every angle, with contestants urged to spew out inanities in camera on camera.

Cas

e in point: in Great Britain, having been force-fed Jade Goodie's life, loves and lazy assumptions, we are now pummelled with incessant updates of her impending death from cancer in a metaphysical Big Brother's house with walls so porous that great swathes of society are osmosing into the diary room. I'm sure I'm not alone in hoping things go well for her in her own hereafter, but do we really need to know about her fiancé's post-prison curfew, his fight with her mother at her hospital bedside or her sinister elevation to the status of national treasure?

e in point: in Great Britain, having been force-fed Jade Goodie's life, loves and lazy assumptions, we are now pummelled with incessant updates of her impending death from cancer in a metaphysical Big Brother's house with walls so porous that great swathes of society are osmosing into the diary room. I'm sure I'm not alone in hoping things go well for her in her own hereafter, but do we really need to know about her fiancé's post-prison curfew, his fight with her mother at her hospital bedside or her sinister elevation to the status of national treasure?A pathological desire to seat oneself in somebody else's sensorium, however, only drives a sub-plot of the book. The main part deals with the desire for eternal deferment of death and its strange bedfellow, the compulsion to self-destruct. This can be seen in two news-stories that are currently in the news.

Last July, I blogged about Dr Iain Kerr, who had been suspended from practicing

medicine for 6 months after being found guilty by the General Medical Council of prescribing large doses of barbiturates to people, mostly older, whose medical presentations did not remotely suggest that barbiturates were appropriate. I then lamented that while Dr Crippen was hung after being convicted of killing one person (his wife), "now a man who is happy to publicise his murderous pastime...is suspended from his profession for 6 months, but otherwise at liberty".

medicine for 6 months after being found guilty by the General Medical Council of prescribing large doses of barbiturates to people, mostly older, whose medical presentations did not remotely suggest that barbiturates were appropriate. I then lamented that while Dr Crippen was hung after being convicted of killing one person (his wife), "now a man who is happy to publicise his murderous pastime...is suspended from his profession for 6 months, but otherwise at liberty".However, Kerr now states that he has cut his ties to Dignity in Dying (formerly the Voluntary Euthanasia Society), and adds, "I appreciate that it is not acceptable for an individual doctor, no matter how well intentioned, to act in those sort of circumstances as an individual...".

But there's a sting in the tail. Immediately following the above statement is: "without the benefit of some formal process governing any sort of activity like this". Kerr elucidates:

I realise that if there is to be any form of physician-assisted suicide, it will have to be within a proper legal framework and that there is no place for a practitioner to become so empathic with a patient that he may be tempted to go contrary to the current advice on physician assisted suicideHe says, furthermore, in the first article linked to, "If the law is to be changed, it must be politicians and lawyers who draft the changes".

His comment is germane to another breaking story, that Debbie Purdy has been unsuccessful in her appeal to secure an undertaking that her husband would not be arrested for abetting her suicide should he help her travel to the Dignitas Clinic in Switzerland. A commercial concern, it makes a lot of money helping people with chronic pain, terminal and/or degenerative illness or depression go gently into that good night. Her original case against the Director of Public Prosecutions, as Joshua Rozenberg explained, was thrown out because the DPP was unable to give an undertaking based on a hypothetical scenario. Tellingly, in relation to Dr Kerr's view that "politicians and lawyers" must pave the way towards the anti-utopia Sheckley novelises, the law-lords have reinforced the point that it isn't a job for lawyers and judges to make law, rather "it had to be parliament which decided if the law should change".

His comment is germane to another breaking story, that Debbie Purdy has been unsuccessful in her appeal to secure an undertaking that her husband would not be arrested for abetting her suicide should he help her travel to the Dignitas Clinic in Switzerland. A commercial concern, it makes a lot of money helping people with chronic pain, terminal and/or degenerative illness or depression go gently into that good night. Her original case against the Director of Public Prosecutions, as Joshua Rozenberg explained, was thrown out because the DPP was unable to give an undertaking based on a hypothetical scenario. Tellingly, in relation to Dr Kerr's view that "politicians and lawyers" must pave the way towards the anti-utopia Sheckley novelises, the law-lords have reinforced the point that it isn't a job for lawyers and judges to make law, rather "it had to be parliament which decided if the law should change".So if the Labour Party takes the bait and legalises physician-assisted suicide, it will certainly win itself a sort of immortality: it will be cursed until the end of history by victims of the liberal totalitarianism which seeks to knock down concepts of objective right and wrong while ever strengthening its belief in its own infallibility.

Yet even the dismissal of the appeal has a sting in its own tail, as Paul Tully of SPUC comments:

Today's judgment, however, is disturbing in that the judges seem to hThis disregard for disabled people can be seen in action even as Sheckley was writing Immortality, Inc. Author Dick Wittenborn recalls a conversation with his pioneering psychiatrist father:ave shown support for the idea that some (disabled) people are right to want to die. The judgment acknowledges the wrongfulness of giving practical assistance to people who want to die, but asserts that it may be "inexpedient to take action against relatives for assisting a disabled person's suicide". The presumption underlying this thinking is that the lives of people who are enduring long-term disabilities are of low value, and should not be protected in the same way as other people.

In the mid-Sixties, after one of my dad's cocktail parties, I told him how cool I thought a colleague of his was...this eminent man of medicine had won the Lasker Award and was then thought on his way to a Nobel. My father answered, 'Yeah, Dr X is a good guy. Of course, he's killed hundreds of his patients.'It sometimes seems overwhelming, so it's good to see good news when it comes in: Wesley Smith of Secondhand Smoke reports that "Hawaii's assisted suicide legislation looks like it isn't going to make it this year."

Sheckley makes a wise move when he has one of his characters announce that the Hereafter Insurance Corporation deals with the mind, and makes no pronouncement on the survival or fate of the soul, something which the Government seeks to deny at every available opportunity through its pet outlets like New Scientist and the BBC.

Out of my parents and grandparents, a group of six people, five died of cancer and the fate of the sixth is lost to posterity, so what life has in store for me is a closed book; like all of us, I guess. But, when all's said and done, the school of thought that believes immortality consists purely of existing as a memory is poor man's meat: there's only one book I want my name in.

Do you know, I've a half-formed theory about the vicarious thrills some seek. I wonder if sometimes those whose souls are dead through serious sin are looking for something to make themselves feel more alive. Tolstoy, I believe, said that all happy people are basically the same (dull to others, I believe he meant) but miserable people are miserable in an infinity of ways.

ReplyDeleteAlso noticed that some people in a state of serious sin enjoy "music" that sounds like zombies speaking. Atonal, is that the word?

Makes me wonder.

Wasn't able to comment on here due to glitches with the blogware the last few days - sorry!

Please don't be sorry - in fact I commented to another blogger that I couldn't comment on his site!

ReplyDeleteI think you're right about the Tolstoy quote - thanks for that, I hadn't heard about that one!

I've noticed that as well about music. I remember a patient in a locked ward with the most caustic views about women, they was disgusting. Turns out, these views were being reinforced by listening to rap music. Once this was taken out of the picture, then slowly not only did his views about women ameliorate, but his illness became more responsive to treatment.